Government agencies and companies across the world hold large amounts of data on each and every one of us. From profiles of your favourite movies to where you ate out last night, this vast mountain of data is a representation of you that you can do little about.

But is that strictly true? Can you find out what GCHQ, Facebook or Google hold on you? And can you get it removed?

Let’s start with the king of data collection in the the UK: GCHQ.

A recent court win by human rights watchdog Privacy International could enable some people to see what the British surveillance agency holds on them, if someone is prepared to go to court for them.

The group won a case with the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT), which declared that regulations covering GCHQ’s access to emails and phone records intercepted by the US National Security Agency (NSA) were illegal – the first time the IPT has upheld a complaint against GCHQ.

The next step is to find out which Brits were illegally spied on. Anyone can apply to the IPT and ask for it to find out from GCHQ whether they were illegally spied on, but Privacy International is making it easier: fill in a simple form on its website and it will apply on your behalf, and fight any resulting court battle.

More than 6,000 people signed up in the first 24 hours after the form was launched, and more than 10,000 in the first two days. “We’ve always believed GCHQ has been illegally spying on people, but it’s never been shown in court,” says Mike Rispoli, communications manager at Privacy International. “So this opportunity is rare.”

The IPT is obligated to respond to any complaints, and reveal if you were illegally spied on or not. If so, you can ask the data be deleted. Rispoli admits the process could take months if not years to resolve, but suggests Privacy International may be prepared to continue to take GCHQ to court if it doesn’t comply.

“GCHQ might come back and disagree with us,” said Rispoli. “We’re very happy to be having that long battle with them because we feel that strongly that this illegality needs to be remedied, and intelligence agencies need to be held accountable for when they participate in illegal activity, and this is one way to do that.”

It’s easy to assume that GCHQ knows everything about us, but it’s important to actually find out, says Paul Bernal, a law lecturer at the University of East Anglia: “It is good for attention to be drawn to the fact that information may be being held about almost anyone.

“In general, it seems that when people know about how their privacy is being invaded, they care more – and much of the current problem, particularly in the UK, is through complacency and a feeling that the ‘nothing to hide’ argument holds water. If they can see their own information, they are more likely to care.

“This kind of campaign is also a way of keeping the issue in the public eye – which is critical,” he added. “GCHQ would probably like this issue to just disappear, and people ‘move on’.”

The Privacy International project hasn’t gone without criticism of its own. As thousands of Brits were signing up, pundits took to Twitter suggesting PI was inadvertently building a list of names for GCHQ to start surveilling, if they weren’t already.

“I think that’s a legitimate concern,” says Rispoli, admitting that when a privacy organisation gathers personal information and then passes it to an intelligence agency, “it raises red flags”. However, the data isn’t going directly to GCHQ, but to the IPT – and he says it’s simply the only way.

“I understand the concern. I would be concerned too. But I think that when you have these types of opportunities, these moments, and you want to stand up to illegal activity, you unfortunately sometimes have to hand over some information,” he says.

“The Tribunal can’t act by itself – it can’t go to GCHQ and say ‘delete all the data that you collected on people’. People actually need to come forward and complain.”

Private firms, private data?

Making a noise in court may be the only way to get information from GCHQ, but the intelligence agency isn’t the only organisation to keep a tight hold on our personal data. If you’re impatient for the results of Privacy International’s attempt to wrench data from GCHQ, you can easily fill the months and years trying to find out who else knows what about you.

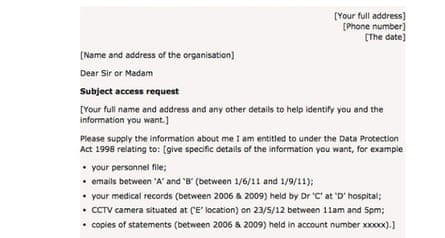

Under the 1998 Data Protection Act, Europeans can ask organisations to hand over details of personal data held about them. You can invoke this law simply by sending a letter or email to the data controller of the company in question. The company has 40 days to respond and can charge you £10.

Data can be exempt from right to access for a wide range of reasons, including national security, interference with criminal investigations, or social and health records that could cause serious physical or mental harm, among others.

Sound simple? It doesn’t mean you’ll get a good response. Many companies fail to live up to the letter of the law, according to a study by Professor Clive Norris of the University of Sheffield.

For the research, he and his colleagues contacted 327 European organisations to see how well they responded to requests for data under right of access. Published last summer, the research found “serial obfuscation” on the part of those contacted: in one in five cases, the researchers were unable to even find contact details for the data controller.

When that could be found, four in ten still didn’t disclose what personal data they held; when data was disclosed, a third of the time it wasn’t everything the organisation held.

On top of that, the vast majority still charged the £10 fee. In the UK specifically, Professor Norris’s report revealed “systemic suspicion” from companies when faced with such requests.

Some of the worst offenders were massive technology firms . Microsoft and Facebook “provided many pages of content regarding privacy but failed to offer users an unambiguous and simple platform through which to make access requests”.

“Given the sheer breadth of personal data collected by these organisations, there would appear to be a deliberate strategy to deny citizens their rights to know how their personal data is being used, processed and shared,” the report noted.

If you’ve asked for your data, and faced the hurdles Norris described, you can complain to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO).

The data protection watchdog not only has a host of form letters and list of data controllers to help you correctly file a right to access request, but it will also investigate any complaints for organisations that fail to follow through fully. In its last annual report, ICO said half of the 14,738 complaints it received dealt with right to access.

Others take it further. Consider Max Schrems. While a student, the Austrian decided to write a paper about how Facebook meets European privacy law after the company’s lawyer gave a talk to his class. In 2012, Schrems asked Facebook for the data it held on him, and was sent a disc of 1,200 pages.

He’s taken the social network to court in Austria, with a class action suit alleging Facebook broke data protection laws. Thousands of Europeans signed up to take part – and like the PI’s case against GCHQ, Schrems believes the support will help put pressure on Facebook.

“With this number of participants, we have a great basis to stop complaining about privacy violations and actually do something about it,” he said in 2014.

How to get (some of) your data

Tech companies do offer ways to get a slice of your data without invoking the Data Protection Act. Head to your General Account Settings in Facebook, and there’s a link at the bottom to Download a copy of your Facebook data.

The site will take some time gathering up the data, but eventually send you an archive of your account, from your posts and photos to ads you’ve clicked, friends you’ve deleted, facial recognition data, IP address and your last location, and even metadata from your photos.

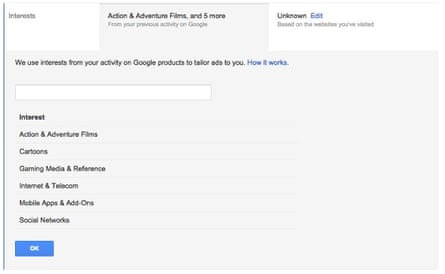

You can get a less detailed, but similar, slice of data from Google via its Dashboard. It tracks locations where you’ve signed in, linked devices, search history and more. You can also find out how it sells you to behavioural advertisers – it’s a bit of a hoot to see if Google guesses your age, gender and interests correctly, but it doesn’t let you see how it comes up with those distinctions.

Twitter also lets you download an archive of your data, mostly made up of your Tweets. To see yours, head to Settings and Account, and scroll down to Request Your Archive.

Such archives don’t disclose all the data the company has on you, however. For that, you’ll have to make a formal request in writing to each company, and as Professor Norris’s research showed, you still likely won’t get everything without a battle.

Why do they make it so difficult? “Generally speaking, both corporates and the authorities try to avoid giving information about the data they hold, because they know … that when people know or understand how their privacy is being infringed, they care more and even take action – avoiding services or using them less, or even making purchasing decisions based on privacy issues,” says Bernal.

“The key here is that we have some power and influence. If companies think we care, they’ll change. That’s what I think is the most important part of the PI campaign – to keep up the momentum of thinking that people care about privacy and surveillance.”

It may feel like hassling everyone from GCHQ to Facebook for your data is a waste of time – but it may actually make a difference.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion