How many times has the colloquialism "Snoopers' Charter" been used in UK parliament? The answer: 63. While many might think that the term was only coined relatively recently by Tory backbencher and privacy campaigner David Davis, its first usage (in parliament, at least) dates all the way back to 1965. However, the phrase's link with terrorism had its debut in the Palace of Westminster in January 1976, some eight years before the 1984 Telecommunications Act came into being—and with it the ability for UK spooks to secretly intercept bulk communications of British citizens.

Last year, that secret was finally disclosed to MPs during the government's latest bid to legislate for what has been ostensibly described as demands for greater surveillance powers for security services, police, and even local authorities in the UK. Even though we now know that security services had—for years—been using a special power to force telecoms operators to hand over "bulk records" of Brit citizens' telephone calls.

Demands for a Snoopers' Charter, however, have stretched over many years, and appeared under various guises with support from both Labour and Conservative governments. During the last administration—a coalition made up of the Tories, and their junior partner the Liberal Democrats—the so-called Communications Data Bill was rejected, only after that junior partner eventually decided to oppose the proposed law on the grounds that it wasn't "workable or proportionate."

Observers, however, see that outcome as being largely a product or quirk of a coalition, rather than as a defining moment when the Snoopers' Charter was ripped up for good. The planned legislation has, in fact, repeatedly pinged back up again after seemingly being knocked down, Weeble wobble-style.

Making a MurdererSnoopers' Charter

For anyone who doesn't know the history of the Home Office's success in convincing ministers of all stripes, under successive governments, to bring this sweeping new surveillance law into force, it would be easy to assume that it's a party-political issue, especially when one considers the Conservative Party. In opposition during the NuLabour years it was heavily critical of the so-called "database state," and very much positioned itself as the party for privacy.

The Tory position shifted radically, however, when the coalition with the LibDems was formed in 2010. NuLabour's bid for a Snoopers' Charter, known then as the Interception Modernisation Programme (PDF), died as then-prime minster Gordon Brown exited Downing Street, only for it to re-emerge under the stewardship of newly anointed home secretary, Theresa May, first with the even-less-catchy name of Communications Capabilities Development Programme (PDF) in mid-2011, and then as the re-branded Communications Data Bill (PDF) a year later. And while tweaks have appeared in those bits of legislation, the thrust of what is being demanded has remained largely intact.

At 9:30 this morning, February 11, a specially convened joint committee of cross-party MPs and peers—who were asked to rapidly examine May's 299-page draft Investigatory Powers Bill (PDF)—will report their findings, and almost certainly call for the proposals to be rewritten. The panel of politicos heard from a range of witnesses during hearings that were hastily sandwiched between the Christmas period, giving the tech industry, privacy campaigners, and others, only a very short window to scrutinise the latest Snoopers' Charter bid.

It's unlikely, though, that the lack of time will lead to the committee insisting that the draft law should be altogether ripped up.

Indeed, there is a clear sense of a mood change. Some might view this as a sort of exhausted resignation: time to largely give in and let this thing happen, perhaps? Privacy campaigners will say that they have helped bring in a more watered down version of the proposed legislation, while still demanding more safeguards. ISPs privately argue that serious uncertainties about costs, and the vagueness of definitions remain, while acknowledging that one single law for everyone to refer to would ultimately be a good thing.

The poison pill: Will it be red or blue?

After today, lobbying will begin for how the legislation should be shaped. But, again, it's likely that there will be only a small window for this horse-trading to take place. It's worth returning briefly to that earlier quirk produced by the Tory/LibDem coalition government—which led to the Snoopers' Charter being mothballed for a short period—because there's a wrinkle to that story.

That poison pill will kill-off DRIPA at the end of 2016. It would mean that, if the Investigatory Powers Bill—which also seeks to repeal and replace part 1 of the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (RIPA)—fails to pass through parliament by that date, then there won't be a communications data acquisition regime in the UK any more. The Home Office will undoubtedly highlight the LibDem's poison pill as a reason to legislate, and to legislate quickly.

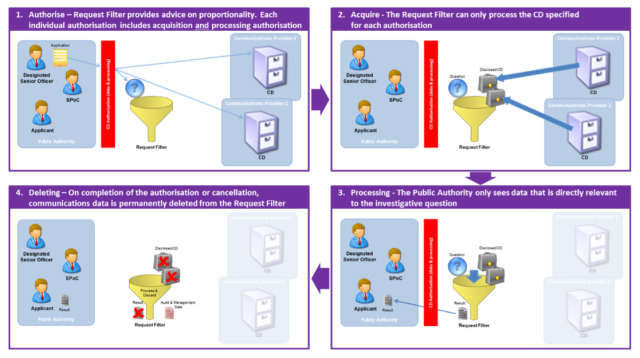

We've already seen a surprising flash of teeth—not only from the science and technology committee—but also from parliament's influential intelligence and security watchdog, so can we expect the same from the panel of MPs and peers who have been poring over the draft Investigatory Powers Bill? And—pushing aside the for and against rhetoric around euphemistic terms such as Internet connection records (logs of Web activity), request filter (distributed database), and bulk equipment interference (hacking)—exactly how much attention, anyway, has been paid to the fine print detailing the powers demanded within the proposed legislation? We're about to find out.

reader comments

3